This tale starts with an introduction to Roy Hobert McPeters, the son of Sampson D. McPeters and Nancy M. Laymance, born in Roane County, Tennessee in 1918 shortly before his father died. Roy’s lineage goes back to Abraham Justice (1790-1860) who married Mahattie Stonecipher (1790-1867). Abraham and Mahattie’s son John Justice (1820-1904) married Nancy Butler (1825-1892) and they had a daughter, Elisabeth Justice, who married Chesley Laymance (1856-1926) and their daughter Nancy M. was Roy’s mother. As I mentioned above, Roy was only a few months old when his father passed away on July 24, 1918, leaving Nancy with several children still at home and under her care. She did have brothers and sisters who lived in the vicinity to help out, and by 1930 she had married again to Joseph Brackett and the younger children had a step-father to provide for them. By the time he was 20 years old, Roy was employed by a company in Rockwood, Tennessee that assembled radios and phonographs. As with many young men of this era of the Great Depression, he decided to enlist in the US Army, and did so in his hometown of Rockwood on December 11, 1939. By April 30, 1940, Private Roy H. McPeters was serving with the US Army in Rantoul, Illinois.

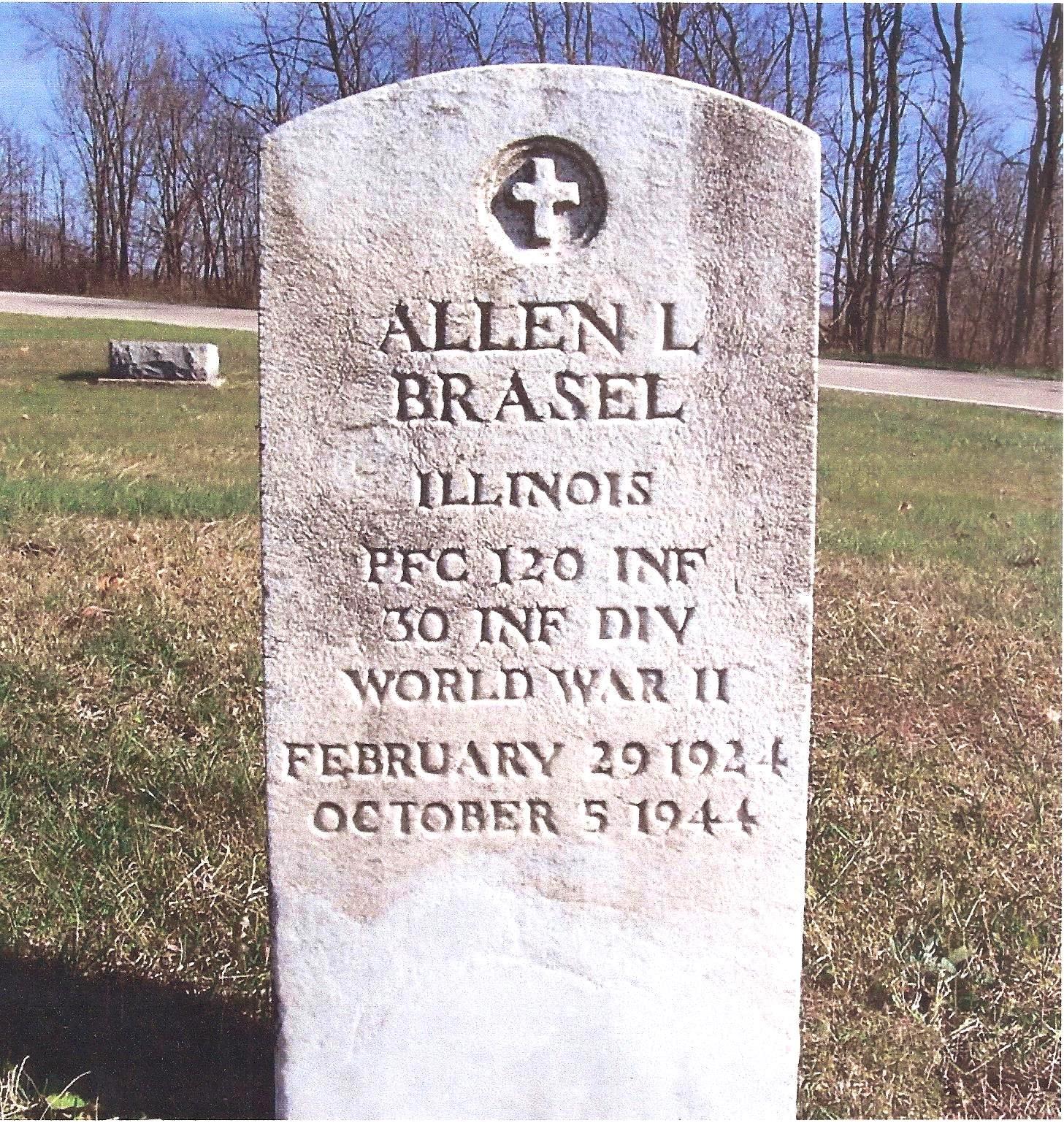

By mid 1940, PFC Roy H. McPeters was transferred to Fort Oglethorpe in Chickamauga, Georgia which is just a few miles across the state line from Chattanooga, Tennessee. While Roy was assigned to Fort Oglethorpe, he met a young lady about his age who had a job as a stenographer with the War Department at the Army base. Shortly after this he received a promotion to the rank of Sergeant in the US Army. Roy and the young lady, Evelyn Tarvin, grew to be very close friends and then fell in love with each other. They spent most of their free time together and had put plans in motion to marry once he was released from the Army.

This photo of Roy and Evelyn was obtained through the graciousness of Evelyn’s daughter who contacted me with a great deal of the information I share here.

By April of 1941, SGT Roy Hobert McPeters was reassigned to Savannah, Georgia, and at this point he and Evelyn began corresponding with each other. He was transferred from Savannah to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas for more training. Then, he spent time at Barksdale Field in Bossier Parish, Louisiana, and it was there that he was assigned to the 27th Bomber Group (Light) in the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron. The group was a part of the V Bomber Command.

B18-A’s and a B18 at Barksdale Field in Louisiana.

In July of 1941, the 27th was transferred to Savannah, Georgia for additional training. While he was training at the base in Savannah, Roy and Evelyn continued to write letters back and forth. After the troops had finished their training, the 27th Bomber Group departed from Savannah aboard the troop transport ship SS President Coolidge in October of 1941, bound for San Francisco, California. The ship had begun life as a luxury cruise ship and spent several years in the service of a cruise line. It was much larger than most transport ships and more fully equipped. While on board the ship on the way to Fort McDowell on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, where SGT McPeters was to be stationed prior to his unit deploying to the Philippine Islands, he wrote a note to Evelyn. The note read, “Dear Eve, This is a picture of the ship I am on. It’s larger than I thought it was. Mac” The note was not mailed until he reached San Francisco.

Troop Transport ship SS President Coolidge. This photo as well as the one above was obtained from Evelyn’s daughter.

By late October of 1941 the troops of the 27th Bomber Group, aboard the SS President Coolidge, had arrived at their temporary home of Fort McDowell on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. During off duty hours, SGT McPeters and the other soldiers were allowed to go across to San Francisco. One of the places that Roy frequented was a Chinese restaurant by the name of Chinese Village on Grant Avenue in the area known as China Town. By November 1, 1941, the troop ship that was to transport the group to the Philippines had arrived. SGT McPeters and the rest of the troops boarded the ship and departed Angel Island bound for the Philippine Islands. The objective of the 27th once they were to arrive at their destination was to do all they could to prevent the Empire of Japan from taking over the Philippine Islands. The 27th Bomber Group (Light) made their appearance at the destination, Luzon Island, on November 20, 1941, however, they had a very serious problem. The aircraft the unit was to fly, A-24’s, which were short range light bombers, had not been able to get a sufficient escort to the Philippines and the ship they were on was diverted to Australia. The entire group was suddenly at a loss to understand what their role was to be now that they were a bomber group without planes. But if the situation was not bad enough, it was about to become even worse. On December 7, 1941, Japanese kamikaze fighter pilots caught the United States naval fleet at Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii completely off guard and destroyed several ships and killed 2403 Americans. On the very next day the Empire of Japan invaded the Philippines because they were certain that the United States would not be able to recover from the losses inflicted at Pearl Harbor. By the 24th of December the soldiers of the 27th, except the actual pilots, were assigned as infantry to fight the Empire of Japan on the Bataan Peninsula.

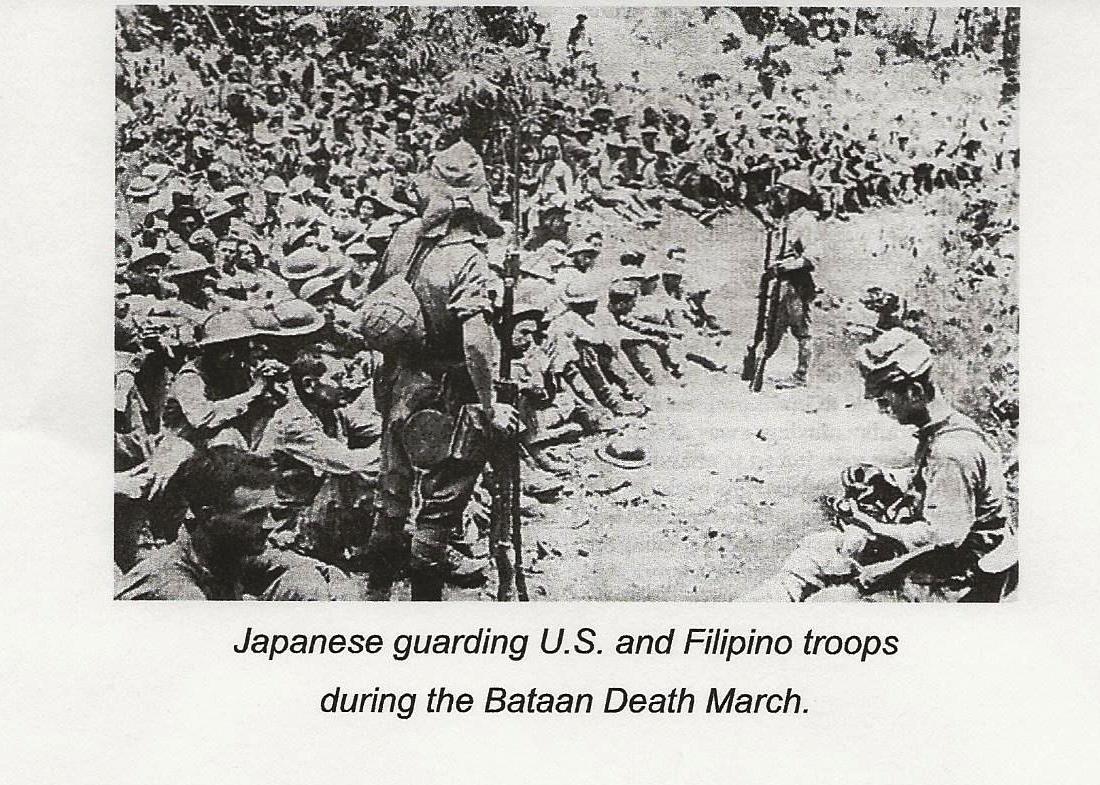

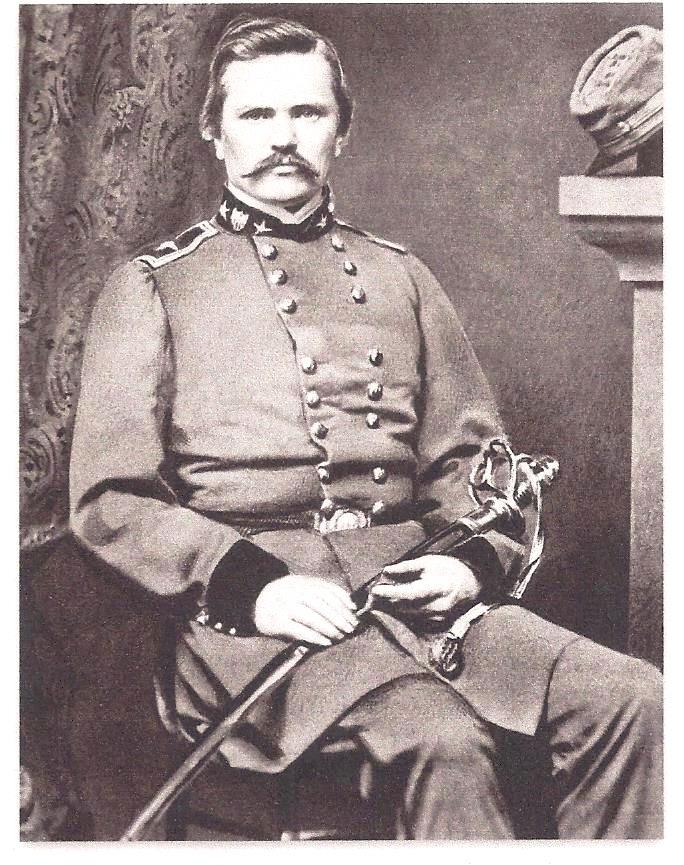

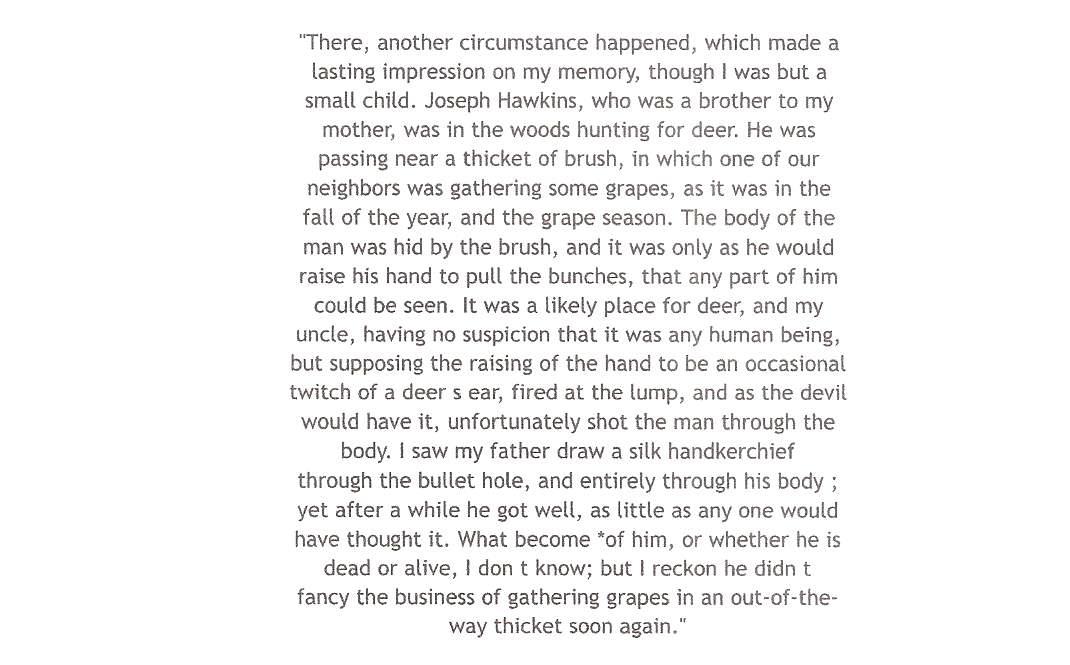

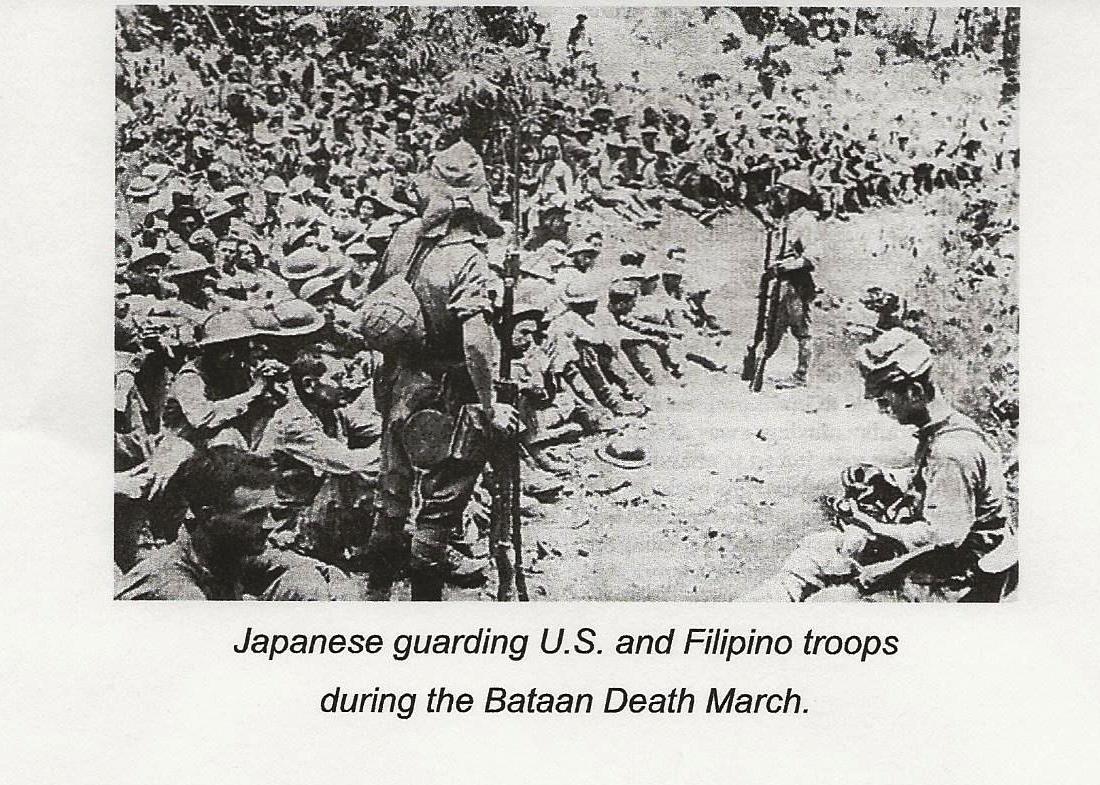

Altogether there were approximately 75,000 United States and Filipino soldiers who had retreated from Manila and other parts of Luzon Island to the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island. Many of the troops, such as the 27th Bomber Group, had no training in actual combat beyond the initial basic training, and yet were issued weapons and ammunition and put in battle immediately. From January through March of 1942, the troops on Bataan and Corregidor fought bravely and well, even though they had no naval or air support whatsoever. Many had succumbed to tropical diseases and diseases related to not eating the right types of food. Others were just on the verge of starvation. Unable to get food and supplies and ammunition, the situation was beyond critical for all the soldiers. Faced with these gruesome facts, the Commander of what was left of the US and Filipino military forces in the Philippines, General Edward King Jr. surrendered everyone under his command to the Japanese on April 9, 1942 on the Bataan Peninsula. The general’s thought was probably that the Japanese would treat their POW’s as Americans treated their POW’s, and nothing could be farther from the truth. What we now know as the Bataan Death March began as soon as the Imperial Army had rounded up all of the thousands of American and Philippine troops. The POW’s were in a forced march from the southern tip of Bataan to the northern part to a town called San Fernando, a trek of about 65 miles. The prisoners were given no food, and little water. At first if someone fell and could not walk on their own, two of the prisoners were required to wrap him in a blanket and carry that blanket on a bamboo pole suspended between them. As the trek continued, the POW’s who fell were just bayoneted and dragged to the side of the road and left. Anyone who tried to escape was shot and killed.

This picture was obtained from The WWII Sinking of the “Shinyo Maru” by Gary Dielman.

The entire march took about five days to complete, and several thousand of the prisoners died before they reached the end. Sergeant Roy Hobert McPeters was one of those who made it all the way to San Fernando, Bataan Peninsula, Philippines.

This photograph from a local newspaper, originally from the Associated Press, was in the files of Evelyn Tarvin and was supplied by Evelyn’s daughter.

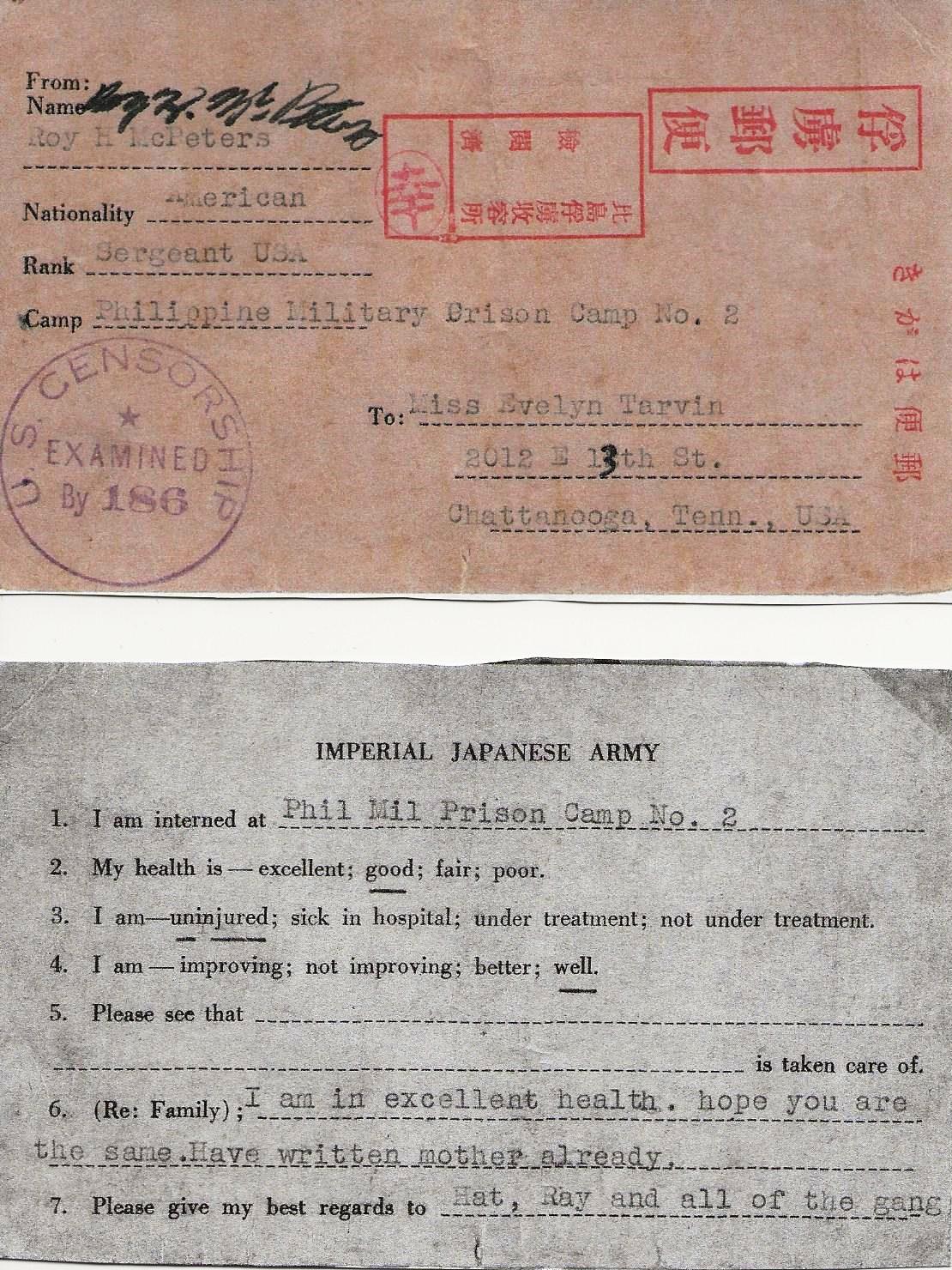

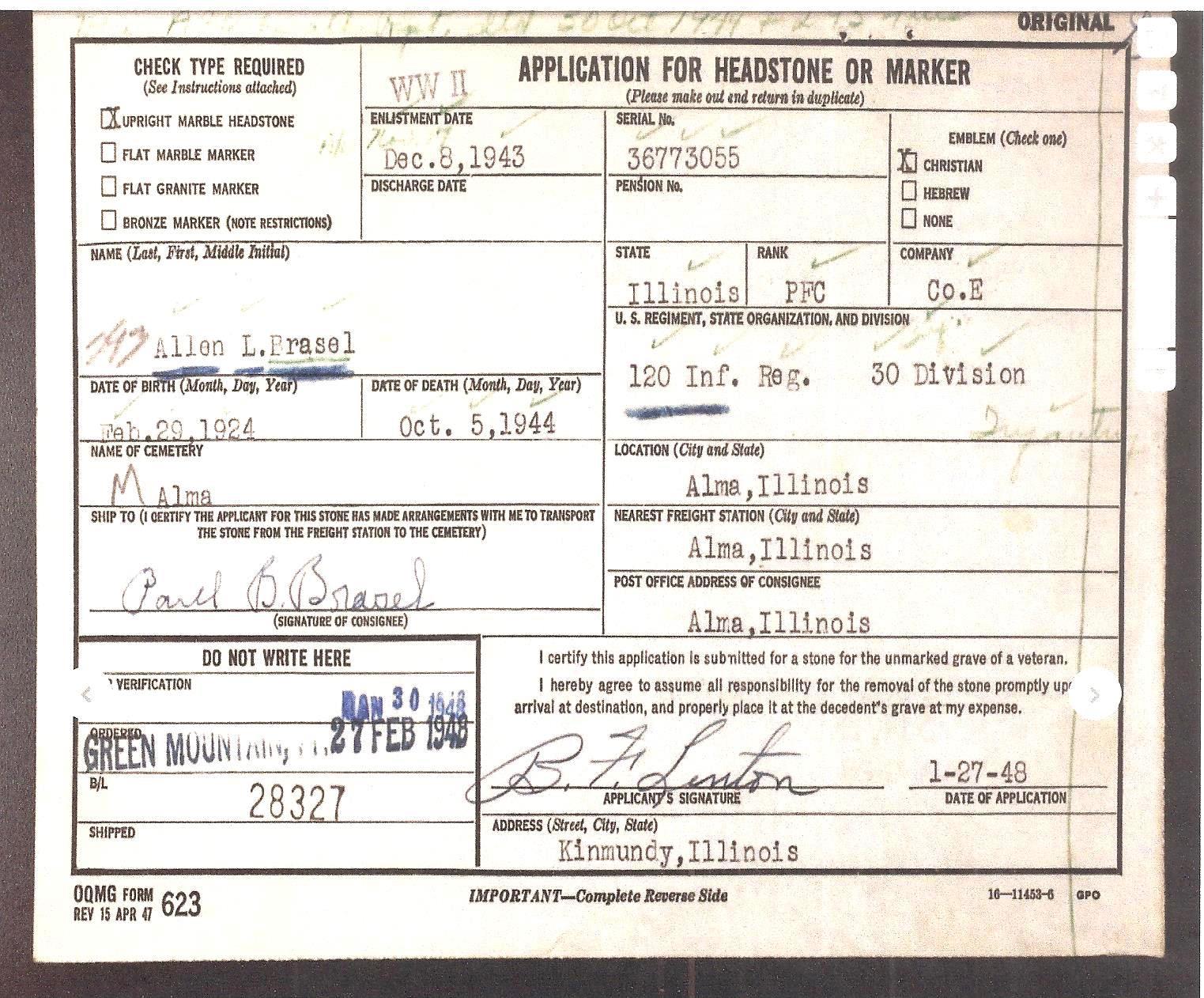

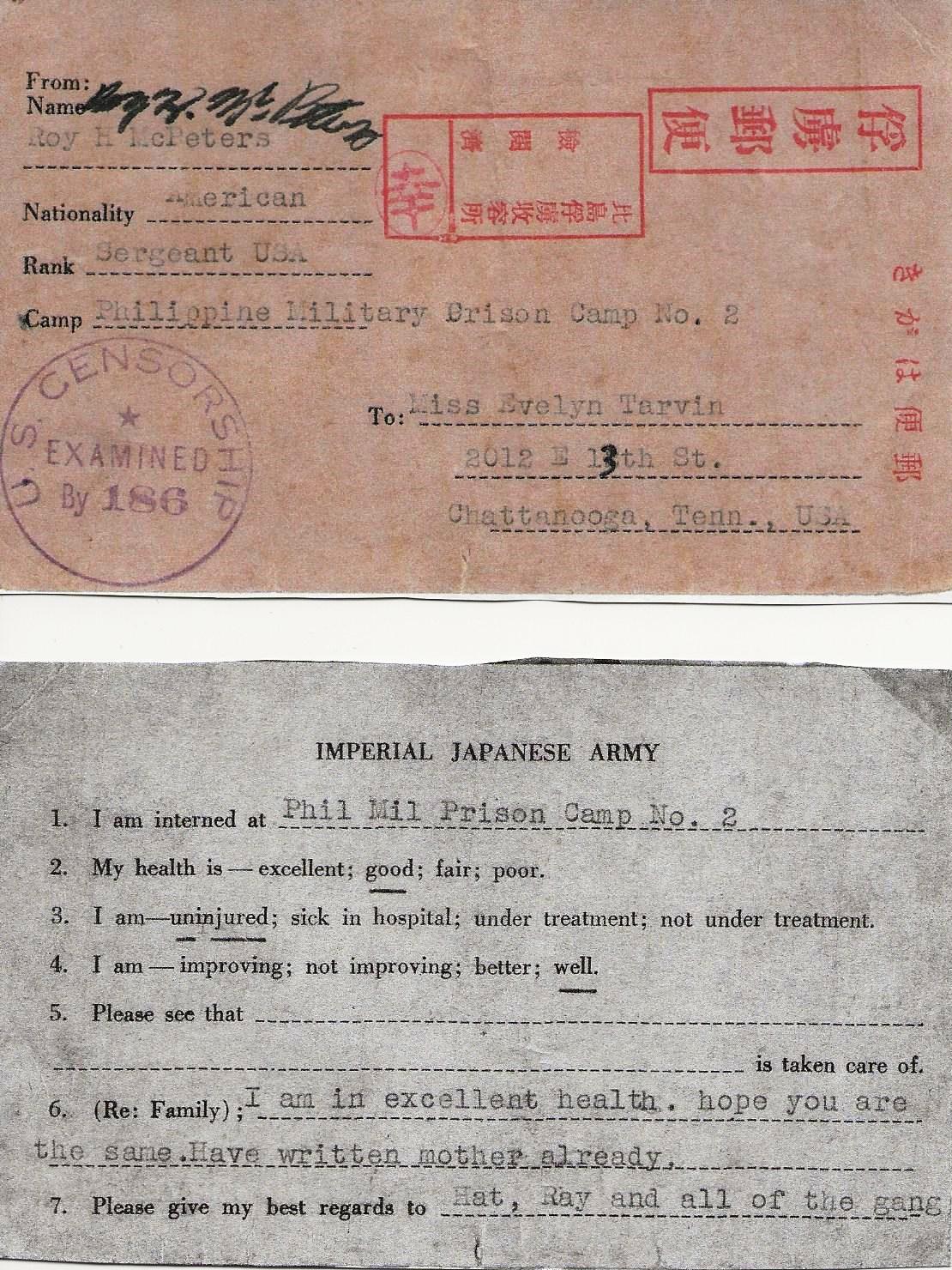

From San Fernando, the prisoners were herded onto boxcars and taken by the railway to Prisoner of War Camps across Luzon Island. Many of the POW’s were near starvation, and many suffered from Malaria and other tropical diseases which the soldiers grouped as one, “Jungle Fever”. Sergeant McPeters was confined to Philippine Military Prison Camp 2. There are sources that declare that this was the POW camp at Camp O’Donnell while some contend that it was POW Camp Cabanatuan. Although I am not sure of the location, I am confident that Roy was imprisoned at Japanese POW Camp 2. The Japanese did not adhere to the rules of the Geneva Convention of 1929 and their prisoners were fed very little and physically abused on a regular basis. The only nutrition they received was rice cooked in a vegetable broth. Occasionally this was supplemented with a minute portion of Water Buffalo meat. By October of 1942, the POW camps were all closed, and the prisoners who had been confined within them were transferred to various locations to serve as slave labor for the Imperial Japanese Army.

This is a post card from Camp 2 that Roy was allowed to send to Evelyn sometime in 1942. It was censored by the Japanese and the US. Each prisoner was allowed to send out about two per year. (Obtained from Evelyn’s daughter)

By the time the Imperial Japanese Army had closed the prison camps, hundreds of the prisoners of war were dying per day from the diseases they had contracted, abusive treatment, and starvation. The photograph below is not of any of the prisoners in Sergeant McPeters’ group, but is of some liberated at another camp prior to that.

This photo from The WWII Sinking of the “Shinyo Maru” by Gary Dielman illustrates how emaciated the POW’s were. Most only had a loin cloth to wear, and no shoes.

Sergeant Roy Hobert McPeters and many other of the prisoners of war were shipped to Davao, Mindanao, Philippines, and made to work constructing a new airfield for the Japanese air forces to use for their bombers and fighters. At night when they were not being used as slave labor, the POW’s were confined in a portion of the Davao Penal facility which housed murderers and other violent criminals. Roy McPeters had survived many battles against the Japanese, surrender, the Bataan Death March, a hideous prisoner of war camp, and yet his situation just seemed to continually get worse.

By March of 1944, the healthiest of the prisoners laboring at Davao were marched to a new POW camp near the village of Lasang. These 650 men, including Sergeant Roy McPeters, began constructing another airfield at the new location. By August of 1944 the slave laborers had made a great deal of progress toward completion of the Japanese airfield near Lasang. It was to their surprise that on August 17, 1944 the United States Army Air Corps bombed that airfield, and gave them and their captors an indication that the Allied Forces might be gaining control in this war being fought to defeat the forces of the Emperor of Japan. A couple of days later, the group of POW’s was marched barefoot and wearing only loin cloths to Tabuaco pier on the Gulf of Davao. On August 20, 1944, Roy and his group of 650 prisoners, plus an additional 100 prisoners, were taken aboard the Shinyo Maru for transport to Tokyo, Japan. The military forces of the Emperor of Japan, fearing an outright American invasion of the Philippines, were ready to transport their free labor to a more secure destination where they could keep them enslaved.

The Shinyo Maru

The Shinyo Maru began life as the Clan MacKay on October 31, 1894. The Clan MacKay was built as a cargo vessel by the Naval Construction and Armaments Company of Glasgow, Scotland. For many years, the Clan MacKay carried cargo for the Clan Lines of Scotland. Between 1914 and 1938, the ship served as a cargo ship in Australia, China, and Greece, and was renamed the Ceduna, the Tung-Tuck, and the Pananis. In 1941 while it was being used as a cargo ship in Shanghai, China, the Imperial Japanese Navy seized the ship. It became a ship used to transport prisoners of war captured by the Japanese in 1943. By this time the Shinyo Maru had been in service under many different names for almost 50 years, a testament to the quality of ships built in Glasgow. The above picture was taken from The WWII Sinking of the “Shinyo Maru” by Gary Dielman. But, to explain further, ships like this one which were used to transport Japanese POW’s were referred to as Hell Ships, and for good reasons. First of all, the prisoners were confined to the cargo holds with no water, food, or sanitary conditions. They were packed in so tightly that they had to take turns sitting and standing. Secondly, there were absolutely no markings to designate them as POW carriers, so they were often attacked by ships, submarines, or aircraft of their own military. This is exactly where Sergeant Roy Hobert McPeters and his fellow prisoners of war found themselves late in August of 1944, aboard a Japanese Hell Ship. There were two cargo holds on the Hell Ship Shinyo Maru, a central hold that was quite large in the very belly of the ship and a smaller cargo hold toward the rear of the ship. 500 of the prisoners were shoved into the forward hold which was below the water level. The other 250 were prodded by bayonets into the smaller hold just below the top deck and at the rear of the ship. The POW’s were confined very closely together in their on filth with many suffering from tropical diseases and diseases like Beri Beri and Scurvy.

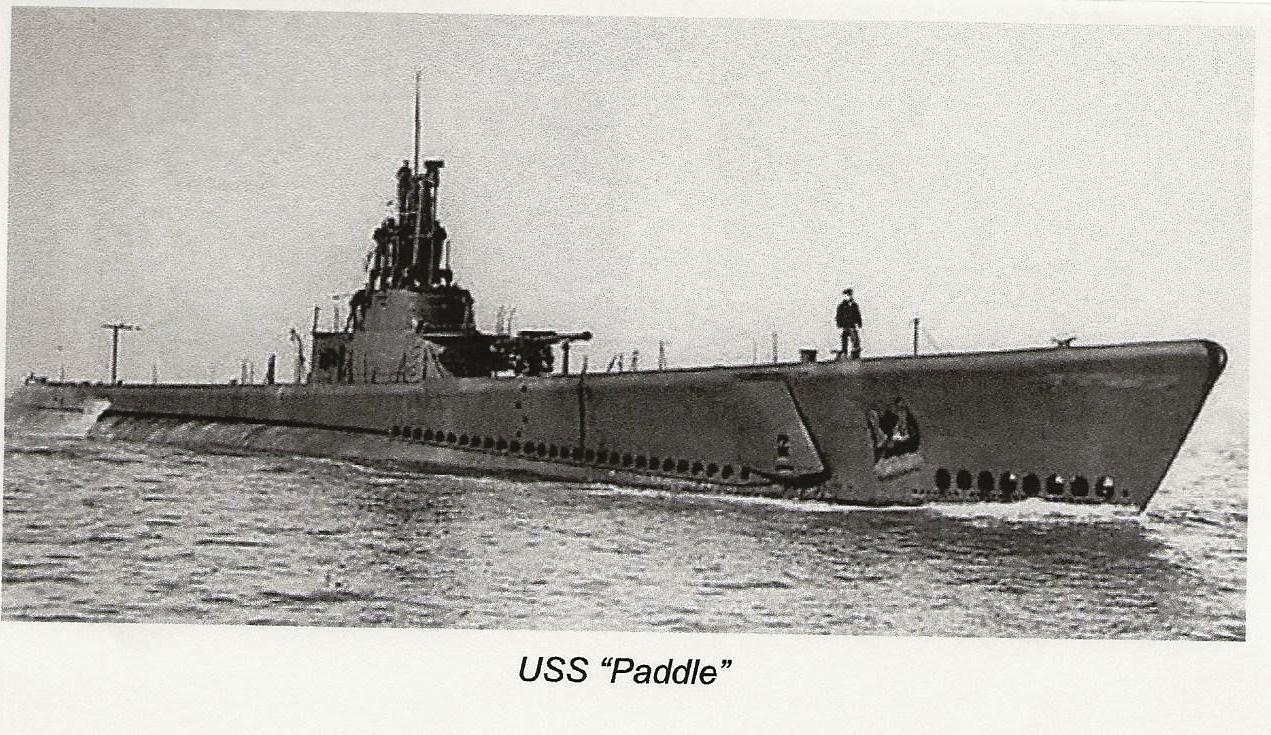

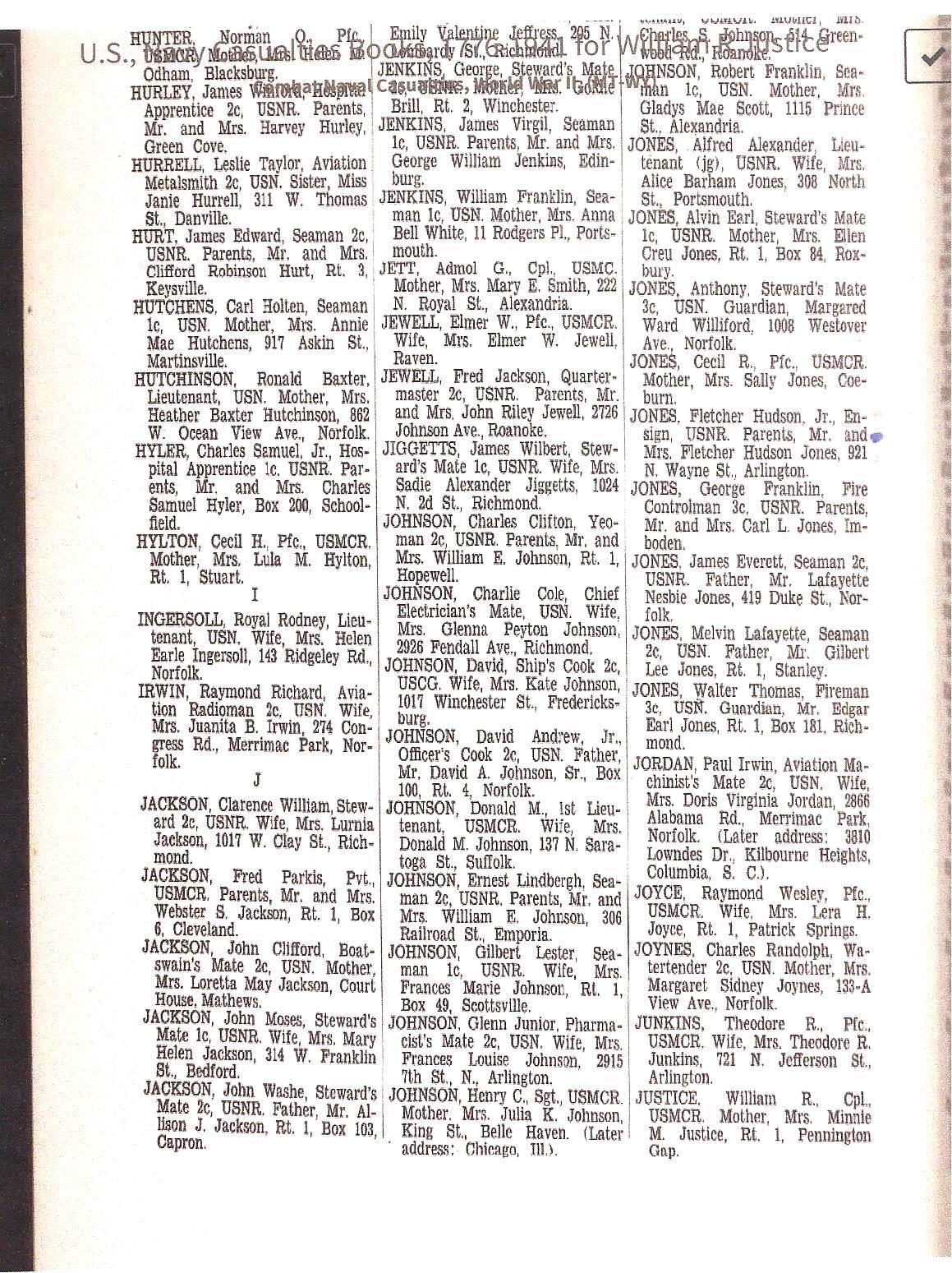

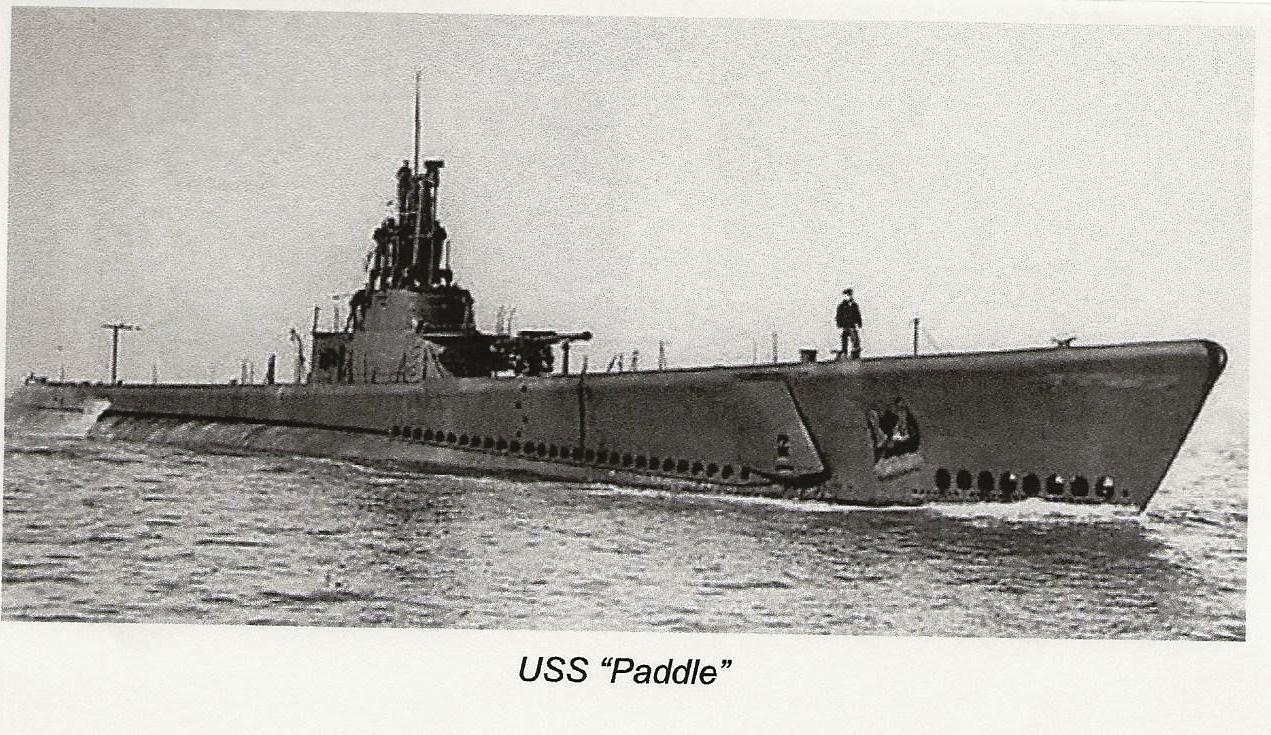

The United States Navy had intercepted two different messages from the Japanese that a convoy was to escort what one message called cargo along the coast of Mindanao Island. The other message referred to the cargo as troops, and was assumed to mean Japanese troops. The USS Paddle (SS 263), a submarine, was assigned to patrol the waters off the coast of Mindanao. On September 7, 1944, while patrolling off the northwest coast of Mindanao, the crew of the Paddle sighted the convoy and attacked. Two torpedoes were fired at one of the tankers and two were fired at the Shinyo Maru. The first torpedo that hit the Hell Ship struck in the forward hold, and those who were not killed by the actual explosion were drowned as water poured in. Some few escaped as the water floated them to the deck. Many of these were shot dead as they attempted to jump off the ship. The second torpedo struck near the other cargo hold. As the Japanese saw what was taking place, some of their soldiers dropped grenades down into the hold killing several of the POW’s, and many more were killed by the explosion of the torpedo. Some of the prisoners jumped overboard through a hole ripped in the side of the ship by the torpedo. Others of the prisoners climbed over mangled bodies to the upper deck and tried to jump overboard from there. Many of these were shot to death by the crew members as they made their way off the Hell Ship, and one of these was Sergeant Roy Hobert McPeters. He had endured so much at the hands of the Japanese soldiers, but as he leaped from the ship he was once again a free man. The ultimate price was paid, but he was free. At the time the torpedoes struck the ship, the Shinyo Maru was just off Sindangan Point, Mindanao. As POW’s attempted to make their way to freedom, the Shinyo Maru began to make a horrendous creaking and metallic cracking noise that could be heard from the Paddle far below in the bay. The Hell Ship buckled in the middle and sank to the bottom of Sindangan Bay. Altogether 83 prisoners of war were able to swim or float ashore using in some cases planks floating in the water. One of those who made it ashore died the next day. The rest were rescued by friendly Philippine civilians who kept the freed prisoners hidden from the constant Japanese patrols. Of the 750 POW’s on board the Shinyo Maru, only 82 survived, and this was indicative of what happened to prisoners on many of the Hell Ships. According to my calculations, there were 12,422 POW’s who died as a result of either friendly fire or murdered by their oppressors while confined to the Hell Ships during the War of the Pacific.

This photograph was obtained from The WWII Sinking of the “Shinyo Maru” by Gary Dielman.

The captain and the crew of the Paddle were never informed that they had mistakenly sunk a POW ship until after World War II was over.

Long before the sinking of the Shinyo Maru, Miss Evelyn Tarvin had begun to receive letters back in the mail that she had sent to Roy McPeters. These letters had been mailed between December, 1941 and April, 1942, and were stamped “Return to sender Service Suspended to this Organization”. At this point Evelyn launched herself on a campaign to try and locate the man she had planned to marry. Using all the connections that she had through the War Department, she sent out inquiries concerning the sudden disappearance of Roy McPeters and his unit. For almost a year and a half, she used every contrivance at her employ to determine what had happened. She would not be deterred. Finally, in March of 1945, Evelyn received the one letter that she had not wanted to ever see. It was a devastating letter from the Adjutant General’s office explaining what had taken place. Now any hope that she had held that Roy might still be alive was dashed. This brave young lady whose quest had ended with the worst of news was suddenly left with an emptiness where love once lived. I have enclosed a copy of the last letter that Evelyn received regarding Roy’s disappearance.

This letter, obtained from Evelyn’s daughter, was kept by Evelyn until her death in 1965 from Breast Cancer.

In conclusion, there are a few final points I want to make. First of all, I will take a passage from an article about the Bataan Death March on history.com. It reads “After the war, an American tribunal tried Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines. He was held responsible for the death march, a war crime, and was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.”

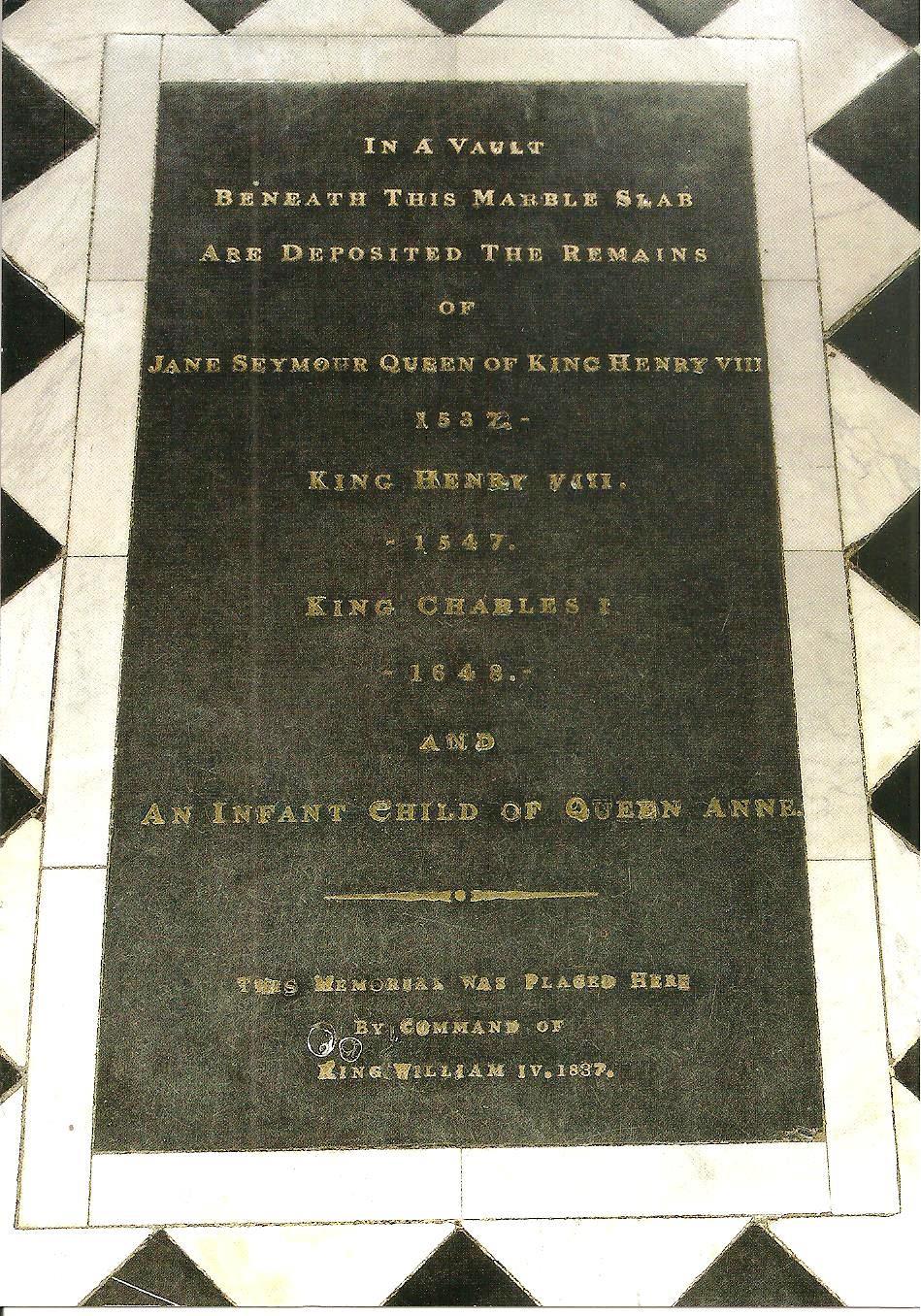

Secondly, I want to bring attention to some memorials. There was one monument to honor those who lost their lives on the Shinyo Maru that was erected at Fort William McKinley, Manila, Philippine Islands. On September 7, 1998, the 54th anniversary of the sinking of the ship, a plaque was dedicated to the survivors of the Shinyo Maru in San Antonio, Texas. Then, on September 7, 2014, on the 70th anniversary, a marker to commemorate the rescue of the survivors of the Shinyo Maru was installed and dedicated in Sindangan, Mindanao, Philippines. I have found no records to indicate that a memorial specifically for Sergeant Roy Hobert McPeters has ever been erected in the cemeteries where his family members are buried.

And finally, I want to make one last statement. I know of no other place in history where such a collection of hubris-infected authoritarians seeking world dominance was ever assembled. I am referring to Emperor Michinomiya Hirohito, Der Fuhrer Adolph Hitler, and Benito Mussolini. Japan, Germany, and Italy formed the Axis Powers in World War II. Hirohito and Hitler were ultimately the ones responsible for the murders of many POW’s, but neither was ever held accountable. These three megalomaniacs came very close to conquering the entire world.

Until next time, I’ll see you on down the road and just around the bend.

Uncle Thereisno Justice

Sources:

The WWII Sinking of the “Shinyo Maru”: A Story of Loss and Survival of Two Baker POW’s by Gary Dielman

Travel Up A travel and adventure blog by Kara Santos

Ancestry.com

American Air Museum in Britain, 27th Fighter Group

National Archives American POW’s on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell by Lee A. Baldwin

Wikipedia Shinyo Maru incident

Roster of Allied Prisoners of War believed aboard Shinyo Maru when torpedoed and sunk 7 September 1944

USS Paddle: Sinking American POW’s by Eugene A. Mazza

Wikipedia List of Japanese hell ships

history.com (A&E Television Networks) November 9, 2009 Bataan Death March

Most importantly, the packet of letters and pictures provided to me by the daughter of Evelyn Tarvin without which the true context of the story would never have been learned. I am most appreciative, but hesitate to use her name without permission.