Around twenty million people died during World War I, which ended on November 11, 1918, with an armistice or cessation of hostilities while the countries involved hammered out a peace treaty. We now observe the day as Veterans Day in the USA, but it was originally called Armistice Day. The Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919 by the combatant countries. Because of too few punitive measures against the invading countries, the “Great War” was followed in a short twenty years by another devastating World War. However, neither of these wars is to be prime target for my parable-like rambling on this Veterans Day. The war that I will concentrate my efforts on today will be the American Civil War.

Before I delve wholeheartedly into my narrative, I need to present some information pertaining to the main focus of this story, John Goddard. John was the great grandson of Joseph Marion Stonecipher, and his parents were Joseph Goddard and Rachel Stonecipher. He was born in Morgan County, Tennessee in 1842, and his father died at Beech Fork in Morgan County when John was only seven. Life in the hills of Tennessee was by no means easy at the time when he and his siblings were growing up, and on top of that he had to work on the family farm at an early age. By the time he was nineteen, the Civil War was in full swing, and John Goddard made his way to Kentucky to enlist in the Union Army. He arrived in London, Laurel County, Kentucky and enlisted as a Private in Company B, 2nd Regiment of the East Tennessee Mounted Infantry on December 5, 1861. A part of the duties his unit was tasked with was to keep the supply and communication lines open from East Tennessee back up into Kentucky.

By 1863, Private Goddard’s unit was stationed as a part of a detachment in an outpost east of Rogersville, Hawkins County, Tennessee. The detachment was comprised of the 2nd Tennessee Mounted Infantry, four guns of Battery M, 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, and the 7th Ohio Cavalry. This detachment served as a part of a chain that was charged with the job of assuring that the supply and communication lines back to Kentucky were indeed maintained and kept open. However, to call what transpired in late 1863 a comedy of errors would be a gross understatement.

Colonel Carter, the commander of the detachment, was given a leave of absence to return home and deal with family issues. Detachment command was then in the hands of Colonel Garrard of the 7th Ohio Cavalry. Lt Colonel Melton, the 2nd Tennessee commander also was home on a leave of absence. His replacement was Captain Carpenter. The commander of the light artillery unit was ordered elsewhere, and that command was left in the hands of an inexperienced lieutenant. Added to all of this was the fact that the detachment had become the primary target for the seasoned forces of Confederate General Jones.

General Jones had split his Confederate forces into a northern and a southern column with the intent of encircling the Union detachment. By the time that a plan of any kind was put into effect by the inadequate Colonel Garrard, the detachment was all but surrounded. The plan that Colonel Garrard had concocted was to make a run for it. He had loaded food and supplies on wagons, and had planned for his 7th Ohio troops to escape leaving the others to fight. He ordered the 2nd Tennessee troops to dismount, tie up their horses, and hold their ground and defend their position to the death. After that command, Colonel Garrard and about half his force made a mad dash to escape having to leave the food and supplies behind. He also left behind the inexperienced Captain Carpenter and his Tennessee troops and the four artillery guns improperly manned. The 2nd Tennessee made an effort to fight the oncoming Confederate troops but soon realized they were completely surrounded and surrendered to the more qualified army of General Jones. In the battle, five of the troops were killed and 608 were captured. The army of General Jones acquired food, supplies, weapons, ammunition, horses, and prisoners. This display of ineptitude on the part of the improvised command of the Union detachment which occurred on November 6, 1863, is often referred to as the Battle of Rogersville, and occasionally the Battle of Big Creek. The soldiers who were captured were marched to the infamous POW camp at Andersonville, Georgia.

As I have said before in another narrative, Andersonville prison was atrocious. Prisoners were exposed to the elements, contagious diseases flourished, lice covered everything, fleas and other vermin were epidemic, there was no source of uncontaminated water, rations were very scarce, and violence was rampant. Of the 608 soldiers who were captured at Rogersville, 418 perished in captivity at Andersonville. On April 16, 1864, Private John Goddard, proud Tennessean and great grandson of Joseph Marion Stonecipher, perished in prison at Andersonville. His cause of death was reported as severe diarrhea. John Goddard from the beautiful hills of Morgan County, was buried in what is now Andersonville National Cemetery at the National Historic Site in Georgia.

Burial Register of John Goddard from Ancestry.com

Headstone for John Goddard at Andersonville National Cemetery

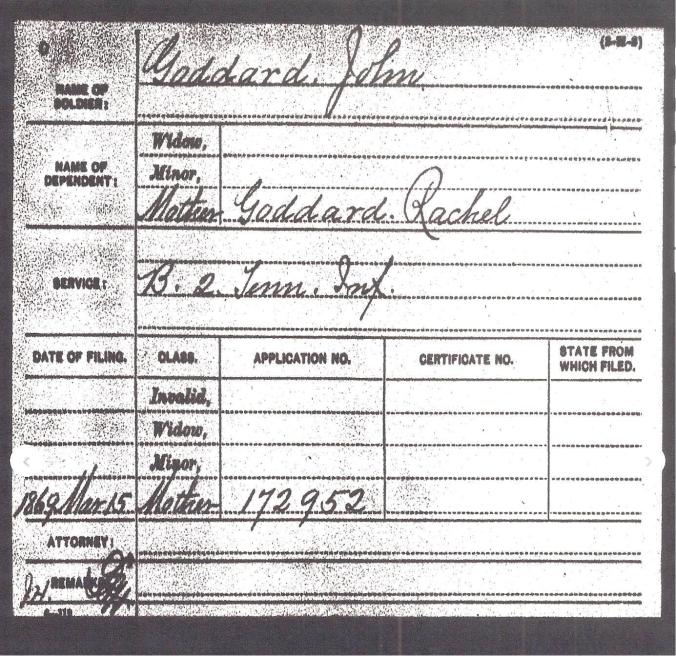

March 15, 1869 pension application of Private Goddard’s mother

My sources for this little story were Civilwarwiki, The Rogersville Review of August 25, 2017, Wikipedia, FindAGrave, and Ancestry.com.

Thanks for taking the time to read this installment, and thanks to all those who have served their country. I hope to see you on down the road.

Uncle Thereisno Justice